Selecting the security controls appropriate for an information system starts with an analysis of the security requirements. The security requirements are determined by:

- An analysis of any regulatory or compliance requirements placed on the system (e.g. regulatory frameworks such as SOX and FISMA in the S., the Companies Act in the UK; privacy legislation such as GDPR in the EU or HIPAA in the U.S.; contractual obligations such as Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard (PCI DSS); or voluntary compliance programs such as ISO 27001 certification or SOC 1/2/3 audits)

- An analysis of the threats the system is likely to face (see the “Understand and Apply Threat Modeling Concepts and Methodologies” section in Chapter 1)

- A risk assessment of the system

In some cases, the analysis of both the threats and any applicable regulatory compliance requirements will specify exactly what minimum set of controls is necessary. For example, the organization that processes primary account numbers (PAN) and handles bank card transactions understands their systems must be PCI DSS compliant. In other cases, such as GDPR compliance, the requirements are more nebulous, and the security architect must analyze the threats, risks, and affected stakeholders to determine an appropriate set of controls to implement.

If an organization has not yet adopted a certain framework, it is beneficial to start with an established information security framework such as ISO 27001, NIST SP 800- 37 “Risk Management Framework,” or the National Institute of Standards and Tech- nology (NIST) Cybersecurity Framework (CSF), ISA624443, or COBIT 5 (to name a few), as this will help ensure that you have considered the full spectrum of controls and that your process is defined, repeatable, and consistent.

Related Product : Personal Data Protection & General Data Protection Regulation Training & Certification

There are a few things to understand about these security frameworks:

- They are not mandatory.

- They are not mutually exclusive of each other.

- They are not exhaustive, i.e., they don’t cover all security concern.

- They are not the same as a standard or a control list.

Now let’s expand on each of those points.

Frameworks are not mandatory. But as an organization adopts or follows a framework, some of the subsequent documents or steps may involve taking mandatory action. Take for example, a company seeking to secure their systems that process credit card data.

When they act according to a framework prompting them to identify their systems and the risks to those systems, the organization will understand they must adhere to the PCI DSS, not a framework but a compliance standard.

Information security frameworks are not mutually exclusive. Many organizations such as the Cloud Security Alliance, ISACA, and the Unified Compliance Framework have developed mappings between the controls in different frameworks, making it easier to achieve compliance with more than one framework at the same time. This might be necessary, for example, when a specific system must meet PCI DSS requirements, but the organization as a whole has selected, say, ISO 27001 as the framework for its information security management system.

Certainly frameworks are not intended to be completely exhaustive. Frameworks can be specialized in either an industry or scope. Take for example, the NIST CSF, which is widely recognized as a general security framework that is applicable for basically any industry. But the CSF does omit one huge security concern: physical security. No mention of entry points is found in the CSF. Along the same lines, other frameworks can be both comprehensive and specialized for a particular field. The Health Information Trust Alliance (HITRUST) CSF is a comprehensive security framework for the healthcare industry.

Lastly, remember not to confuse a framework with a standard or a control list. Frame- works, control lists, and standards are three different concepts. You will likely find a list of controls in a framework. For example, the set of controls included in the aforementioned HITRUST specifically strives to marry the HITRUST CSF with standards and regulations targeting the healthcare industry. Perhaps the best example is NIST 800-53, which is a list of security controls that is so extensive that it is sometimes confused with being able to stand alone as a framework. It cannot. Similarly, there is a marked difference between frameworks and standards. While a framework is an approach or strategy to take, a standard is a set of quantifiable directions or rules to follow. In most organizations, the standard would logically follow the policy, just as mandatory instructions would follow a decree stating what is mandatory.

What all frameworks have in common is an all-embracing, overarching approach to the task of securing systems. They break that task down into manageable phases or steps. For example, at the highest level, NIST Special Publication 800-37, “Risk Management Framework,” breaks down the task of securing a system this way: starts with categorizing the system (based on impact if that system’s security were affected), identifying the proper security controls, implementing those controls, assessing their impact, and then monitoring or managing the system. From this breakdown, security controls are the obvious central point involved in securing the system. These controls are the real tangible work performed from adopting a framework. Due to the broad reach and depth of controls, there are whole catalogs or lists available.

Once you have selected your framework, you need to review all of the controls to determine which are appropriate to address the risks you have identified. In some cases, the framework itself will provide guidance. For example, NIST SP800-53 provides three levels of controls, called “Initial Control Baselines,” based on the risk assessment. Threat modeling and risk assessment will also provide information on which controls are most important and need to be implemented with higher priority than other controls that address vulnerabilities with a low likelihood and impact.

Implementing all of the controls in your selected framework to the same level of depth and maturity is a waste of time, money, and resources. The general objective is to reduce all risks to a level below the organization’s risk threshold. This means some controls will have to be thoroughly and completely implemented while others may not be needed at all.

Often, the framework will incorporate a security standard with a minimum set of security controls forming a recommended baseline as a starting point for deployment of systems. Scoping guidance within the baseline identifies the acceptable deviation from control and results in a tailored system deployment that meets the organization’s risk tolerance.

As important as making a considered decision on which controls to implement and to what degree, is to have a formal process for making such decisions (from threat modeling and vulnerability assessments, through risk management, to control selection) in which you document the path to your decisions and the information upon which you based your decision. Implementing a defined, repeatable, and industry-accepted approach to selecting controls is one way the organization can demonstrate due care and due diligence in security decision-making.

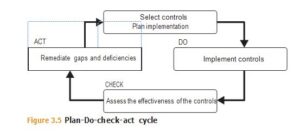

Of course, selecting controls is just the beginning. You need to:

- Consider the control and how to implement and adapt it to your specific circumstances (the “Plan” phase)

- Implement the control (the “Do” phase)

- Assess the effectiveness of the control (the “Check” phase)

- Remediate the gaps and deficiencies (the “Act” phase)

This Plan-Do-Check-Act cycle (also known as PDCA or the Deming cycle) is, of course, an iterative process. This was explicitly pointed out in ISO 27000:2009, but only implied in later editions. Other frameworks, such as the NIST Risk Management Frame- work, also leverage the continuous process improvement model to shape the efficiency and effectiveness of the controls environment. See Figure 3.5.

On a more frequent basis you need to (re-)assess the effectiveness of your controls, and on a less frequent basis (but still periodically) you need to reexamine your choice of controls. Business objectives change. The threat landscape changes. And your risks change. The set (and level) of controls that were appropriate at one point of time is unlikely to be the same a year or two later. As in all things related to information security, it is certainly not a case of set and forget.

In addition to the periodic review of the control selection, specific events ought to be analyzed to determine if further review is necessary:

- A security incident or breach

- A new or significantly changed threat or threat actor

- A significant change to an information system or infrastructure

- A significant change to the type of information being processed

- A significant change to security governance, the risk management framework, or policies

Frameworks are also updated, and when they are, one needs to consider the changes and adjust as appropriate.

Follow Us

https://www.facebook.com/INF0SAVVY

https://www.linkedin.com/company/14639279/admin/